A takedown of the Stanford study claiming humans age faster at 44 and 60

The researchers and Stanford's communications department overstated their conclusions and let major media do the same, trading nuance for juicy but misleading headlines. Here's how and why.

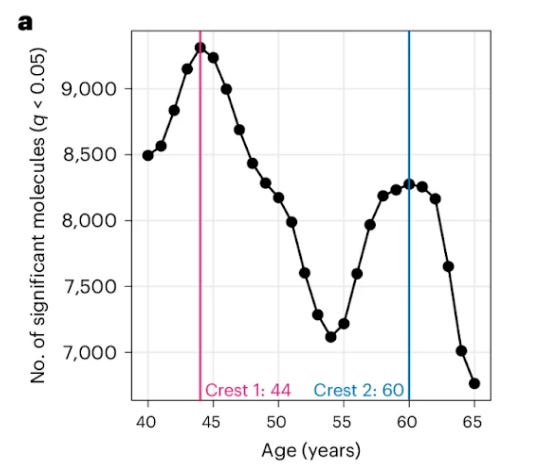

On August 14, Stanford researchers reported what seemed like a blockbuster finding: humans age much more rapidly at 44 and 60 years. Within hours, news articles and TV segments erupted across the internet like opium poppies in the Afghan spring. The collar-grabbing headlines were unanimous in pronouncing a new pan-human fact of life.

CNN: “Humans age dramatically at two key points in their life, study finds”

CBS News: “Humans go through 2 rapid bursts in aging, study finds”

The Guardian: “Scientists find humans age dramatically in two bursts”

Fox News: “Aging speeds up 'massively' at two points in one's lifetime, Stanford study finds”

Washington Post: “Your molecules change rapidly around ages 44 and 60”

And not least, from Stanford Medicine’s communications department: “Massive biomolecular shifts occur in our 40s and 60s, Stanford Medicine researchers find”

These statements overstate what the study actually found. Stanford’s comms team appears to have oversold the public on what the science showed, in what looks like a two-step that is all too common in the world of grant-funded research. The news media, for its part, failed to notice the disparities between the researchers claims and what their data actually supported, which they noted in the fine print.

One detailed reading of the study, published in Nature Aging, would have revealed most of the hype. Instead, Stanford got major-media coverage for research that future donors will surely notice (and potentially reward), and the news companies banked lots of revenue-generating clicks.

The losers, of course, are people like you and me, the nonexperts who reasonably assume Stanford and CNN et al. would accurately inform us about research on a topic as important as human health and longevity. Some people are going to change their dietary, exercise or life regimens based on the misleading headlines this research generated. Unfortunately, the study, like so many others on human health and well being, is not everything its authors and corporate champions claim it is.

What the Stanford aging study found

To study the aging process, the researchers collected biological samples from 108 healthy people aged 25 to 75 for a median of 1.7 years (ie, 20.4 months), amassing more than 246 billion data points to determine how they aged on a molecular — and only on a molecular — level. It turned out that the majority (81%) of the observed molecules tended to undergo rapid changes in those participants aged 44 and 60 years old. The implication being that humans may age not linearly but in fits and starts. Interesting!

How these molecular changes affected participants in their 40s and 60s

Among the participants who were in their 40s, researchers saw significant changes in molecules related to their ability to metabolize alcohol, caffeine and lipids (aka fat); as well as those related to cardiovascular disease and to skin and muscle. Among the study participants who were in their 60s, major molecular changes occurred in their carbohydrate and caffeine metabolism; immune regulation; kidney function; cardiovascular disease; and skin and muscle.

So far, so good. The study offers compelling evidence that rapid molecular changes among the segment of these 108 people who were in in their mid-40s and at 60 correlate to aging.

But it didn’t examine why those rapid molecular changes occurred around the ages of 44 and 60. And here’s where the sweeping statements about how this study shows that all humans age rapidly at 44 and 60 break down under scrutiny.

Mea culpa: I failed to respond to Stanford’s reply to my interview request

In early October, I reached out by email to Stanford Medicine’s communications team as well as the study’s lead researcher for comment. To his great credit, the researcher, Dr. Michael Snyder, and his assistant each responded to my email promptly. But I didn’t see their replies, because of the way I set up my email inbox, until early December. Dr. Snyder had made himself available to discuss how he and others characterized the study’s findings. I regret my oversight, which wasn’t fair to Dr. Snyder and his colleagues. On Dec. 6, I interviewed Dr. Snyder about this study.

Why the Stanford aging doesn’t show what its authors, and Stanford Medicine, and the media, claim it shows

Here are the specific problems with how the study, its authors and others have distorted the applicability of this research to humans generally:

The small, non-diverse group of study participants is wildly unrepresentative of most Americans, not to mention most humans. 108 people is a small cohort on which to stake a broad claim about distinct aging patterns in all of humanity. In addition to the number of participants, it turns out that all of them were local to the Stanford University area — and thus representative of only the kind of people found around elite, private California university campuses in the heart of Silicon Valley. Third, though the study authors stated the cohort represented “diverse ethnic backgrounds,” a full two-thirds of them (71 of 108) are white and another fifth are Asian. Only 7% of participants are black; 3% are hispanic.

Maybe that’s why, much farther down in the study, the authors cover their backsides by saying “it is important to acknowledge that our cohort may not fully represent the diversity of the broader population. The selectivity of our cohort limits the generalizability of our findings.” 🤔

The study tracked that small, unrepresentative cohort for a very short time. The authors twice refer to their study as taking place “over several years,” but in fact it tracked participants for a median period of only 1.7 years (aka 20.4 months), with one participant — one out of 108 — who was tracked for 6.8 years. Deep in the study’s fine print, the researchers admit 1.7 years of median study is “inadequate for detecting…changes that unfold over decades throughout the human lifespan.” That didn’t stop Stanford Medicine’s communications department from repeating the “several years” claim in its own post about the study, which led virtually all the news articles about the findings to also state that the research covered “several years” of observation, which gave the public a false impression of this being a deeper, longer study with results that are better than “inadequate.” 😞

Researchers call the study “longitudinal”…when it really wasn’t. Over the relatively short 1.7-year median period in which the researchers tracked participants, they collected biological samples every 3-6 months, which correlates to collecting between only 3 and 7 samples per median participant. As Peter Attia, who has become America’s longevity doctor, put it in his own, damning recent critique of this Stanford aging study, “That is not nearly enough time to collect any meaningful results about biological markers that might change with aging.” 😡

(Conspicuous by its absence in his post about the study was any reference to Stanford, where Dr. Attia earned his medical degree.)

The researchers say their study shows all humans age rapidly around two distinct ages, but then concede that “these findings might be shaped by participants’ lifestyle—that is, physical activity and their alcohol and caffeine intake.” In other words, because the study remained focused solely on molecular changes in participants, the researchers have no insight into why those observed changes in the pace of aging occurred around ages 44 and 60 — or even whether those changes are the cause or the result of specific behavioral and lifestyle influences (which are most certainly not shared by all humans). These could include changes in stress levels, physical activity, the type and frequency of physical injuries, emotional changes, alcohol use and dietary habits that many (but hardly all) people in their mid-40s and early 60s typically experience.

That’s why reading different explanations about the study’s findings can be confusing. In the Stanford Medicine post about the study, the study’s lead author, Daniel Snyder, characterized the results as applicable to all humans: “We’re not just changing gradually over time; there are some really dramatic changes,” he said. “It turns out the mid-40s is a time of dramatic change, as is the early 60s. And that’s true no matter what class of molecules you look at.”

But what if you look beyond only the molecules? And beyond the 108 Stanford-area participants in this research? You may well see evidence that behavioral changes at these two age inflection points may be influencing the rapid aging of all those molecules, instead of the other way around. As Dr. Snyder told the Washington Post, “We don’t always know what’s cause and effect.”

Where does that leave us, then? Are the rapid molecular changes Snyder et al. observed (for only 20.4 months, among only a handful of mostly white people in Stanford, California) therefore intrinsic to aging — an inevitable biological shift that were are all fated to experience — or could those observed accelerations in aging be caused or exacerbated by idiosyncratic lifestyle shifts in diet, exercise, stress, injury, caffeine or alcohol that, btw, many many other humans might not experience at all?

The answer from the Stanford study authors seems to be “Yes.” 🤯

Keep in mind, this is a peer-reviewed study published in a respected scientific journal, notably under much more modest title (“Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging”). That its authors were allowed to play loose with their conclusions says something about the state of academic research and where its priorities often lie. If Stanford Medicine chooses to milk the news media for the most donor-forward headlines it can get, to effectively deceive the public about what the science supports, then who will stand as your champion, dear reader? 🧐

Which, btw, is a great argument for the Aging with Strength value proposition. If I hear from the researchers or their flaks, I’ll let you know.

Happy birthday to my late dad. He would have been 85 today.

What did you think of this article? Please leave a comment below. Thanks for reading.

Thank you for the clarification and the ability to cut through the static (as usual).

Thanks for this. The original study came out the week of my 60th birthday and it was quite a downer.