"Organ aging": Two hidden gems in Stanford's new research on humans

Some organs are more likely than others to confer either greater longevity or risk of dying early, depending on how biologically old or young they are.

Takeaways up front:

∞ certain human organs, each of which ages at a unique rate, are associated with either greater longevity or mortality risk, depending on the organs’ biological ages, according to a Stanford research paper

∞ of 11 organs tracked in more than 44,000 people over several years, the brain and immune system, together, uniquely correlated to disease-free human longevity

∞ except for the brain and immune system, having 5 to 7 other biologically “younger” organs actually correlated to an increased risk of mortality; and having 8 or more “extremely aged” organs increased the chances of dying early by what scientists often refer to as a shit ton

∞ of 137 drugs and supplements examined in the research, only six (see below) were “significantly associated” with having at least two youthful organs, which conferred slightly greater than average longevity

“A youthful brain and immune system are key to longevity”

In a convincing and slightly fascinating1 research paper, a group of Stanford University scientists studied the biological ages of 11 organs, over many years, from 44,526 people aged 40 to 69 whose blood and other sample tissue is stored in the U.K. Biobank2. What they learned is, to anyone in the latter half of life, worth understanding.

In this post, I reveal a couple hidden gems from that paper that I haven’t seen in any other published review of it.

But first, the paper’s noteworthy main finding:

“Surprisingly, brain aging was most strongly predictive of mortality,” the researchers wrote in their paper, which was published in June (but has yet to be peer reviewed), “suggesting that the brain may be a central regulator of lifespan in humans.” In fact, the study authors added, people with aged brains showed increased risk for several diseases beyond dementia, including serious lung disease and heart failure, “consistent with previous studies showing that the brain regulates systemic inflammation.”

To track how each of these 11 organs (brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, immune system, arteries, intestines, muscle and adipose tissue aka fat) aged over many years, the researchers tracked proteins produced by each organ.

To get a broader picture of what the research examined, I urge you to read this Washington Post article, by my former NYT colleague Gretchen Reynolds.

On to the two hidden gems in the paper’s findings that, to my surprise, haven’t been noted elsewhere:

Though biologically younger organs are better than having what the researchers called “extremely aged” organs, it turns out that having several younger-than-average organs actually correlated to a slightly greater than average mortality risk.

Of the 137 drugs or supplements the researchers tracked in the Biobank’s longitudinal data, only 6 — Premarin (a brand-name estrogen medicine), ibuprofen, glucosamine, cod liver oil, multivitamins and vitamin C — were significantly associated with having two or more youthful organs. Which, in turn, correlated to having slightly greater than average longevity.

Let’s look at each of these findings in greater detail.

1 | Two graphics that correlate organ age and mortality risk

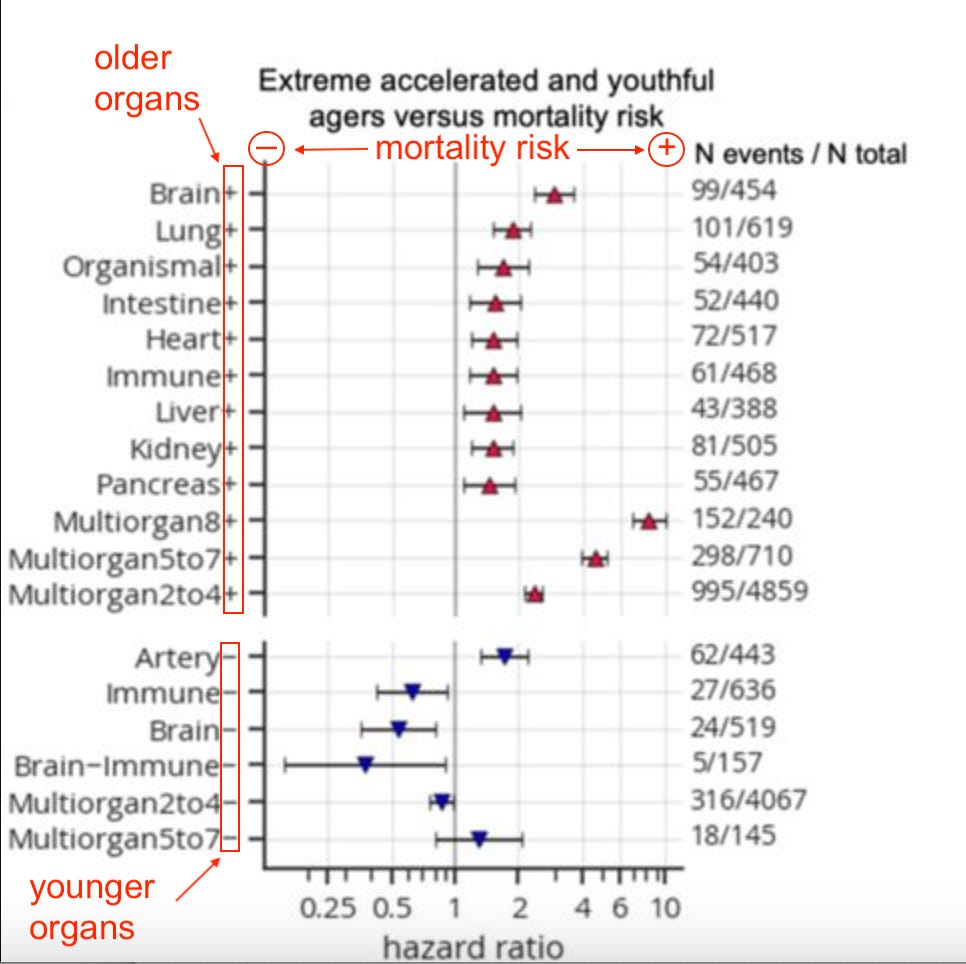

In their paper, the Stanford researchers include two charts that visually summarize how biological organ age is associated with human mortality and longevity.

The chart below shows the impact on mortality risk of each “extremely aged” organ as well as the impact of extremely youthful organs. You can see that the combination of an extremely youthful brain and immune system, for example, has by far the strongest correlation to increased longevity; conversely, people with eight or more extremely old organs were at the highest risk for dying earlier than normal. (To understand how much mortality risk increases for each really old organ or combination of old organs, read this footnote.3)

But then notice the counterintuitive results:

As the researchers4 wrote, “We found individuals with youthful appearing arteries had increased mortality risk, and those with multi-organ youth had no difference in mortality risk compared to normal agers.” (Italics are mine.)

“Multi-organ youth” doesn’t help you live longer?

It may not. According to the data, having a lot of extremely youthful organs is a greater mortality risk than having a couple very youthful organs.

The possible reasons for that are not covered in this paper. Apparently, it’s complicated. But if you trust AI to give you some reasonably sound food for thought, here are some possible explanations.

I’d rather be the blue line than the black. Yes I would.

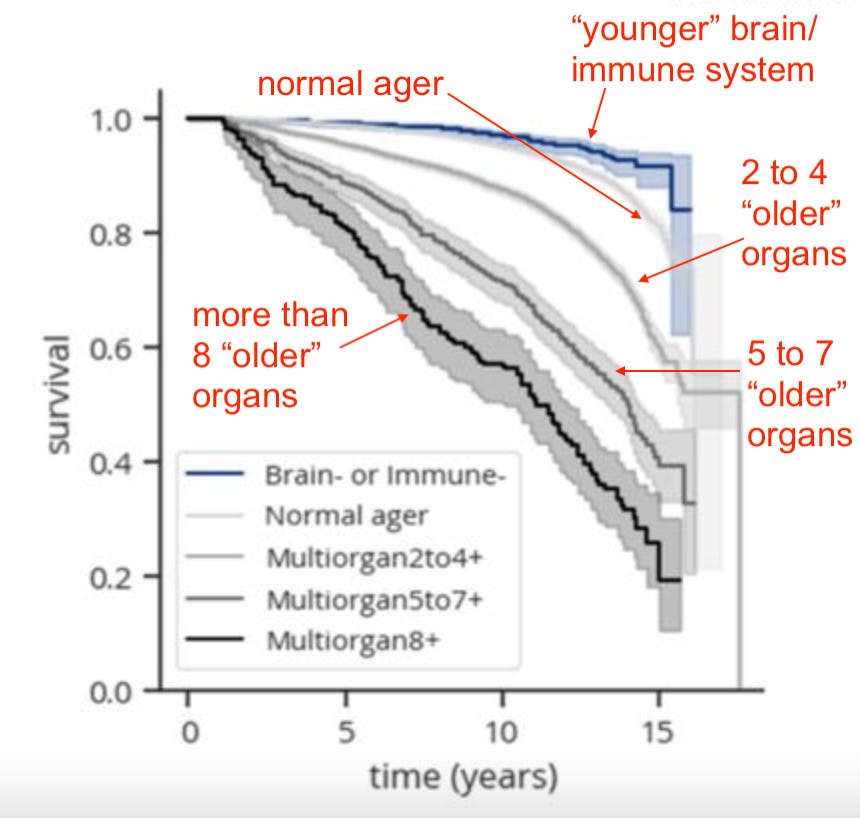

Now, take a look at the graphic below, Fig. 4e from the study, which shows that “the accrual of aged organs progressively increases mortality risk,” the researchers write, “while a youthful brain and immune system are uniquely associated with disease-free longevity.”

By any measure, the blue line is the one to ride.

2 | Five supplements and an estrogen med for younger organs

The correlation of younger organs to the use of Premarin, an estrogen medicine prescribed to women experiencing post-menopausal symptoms, is not surprising.

“Women with earlier menopause were age accelerated across nearly all organs, in line with the well-documented adverse health consequences of early menopause,” the research paper noted. “Conversely, estrogen treatment was associated with more youthful immune systems, livers, and arteries suggesting intervention with estrogen treatment may protect these organs from menopause-induced age acceleration resulting in extended survival.” Here’s the paper’s full passage on this subject.5

Ibuprofen, glucosamine, cod liver oil, multivitamins, and vitamin C “were associated with youth primarily in the kidneys, brain, and pancreas,” the paper said, without elaborating further. Perhaps the anti-inflammatory properties in ibuprofen and glucosamine help reduce chronic inflammation associated with organ aging; likewise, maybe the antioxidant properties in vitamin C and omega-3 fatty acids in cod liver oil help protect cells from oxidative stress, another big factor in the biology of aging.

I guess I’d rather eat a salmon than a steak. Yes I would.

When it comes to medical research, I don’t think it’s oxymoronic to say “slightly fascinating” when the findings are a blend of “Woah!” and “No shit, Sherlock.” For example, the published Stanford organ-aging paper notes, in its fourth sentence, that far and above any other human organ, “a youthful brain and immune system are uniquely associated with disease-free longevity” — Woah! And it also determined that “the accrual of aged organs progressively increases mortality risk” — No shit, Sherlock.

“UK Biobank is a large-scale biomedical database and research resource containing genetic, lifestyle and health information from half a million UK participants. UK Biobank’s database includes detailed information about the lifestyle, physical measures, as well as blood, urine and saliva samples, heart and brain scans, and genetic data for the 500,000 volunteer participants aged between 40-69 years in 2006-2010. It is globally accessible to approved researchers who are undertaking health-related research that’s in the public interest.” (This description is courtesy of University of Oxford.)

According to Fig. 4d, having a single extremely aged organ excluding brain or lungs created a roughly 1.5x increased risk of mortality. (Older aged lungs increased mortality risk by almost 2x; having an old brain increased it by 3x.)

Having two to four extremely aged organs increased the chances of dying to 2.3x. Having five to seven very old organs increased mortality risk by 4.5x.

Among the people whose initial blood draws had showed eight or more extremely aged organs (recall that the 44,526 people included in the U.K. Biobank were 40 to 69 years old), 60% died within 15 years of their samples first being taken, the researchers wrote.

The paper’s Abstract discloses a “competing interest statement” that indicates three of the eight Stanford researchers are also co-founders of and scientific advisors to Teal Omics Inc., a biotechnology company focused on developing treatments for age-related diseases. One of those three is also a co-founder and scientific advisor of Alkahest Inc., a clinical stage biopharmaceutical that is also developing age-related disease therapies.

“Premarin is a conjugated estrogen medication typically prescribed to women experiencing post-menopausal symptoms, and estrogen medication has been recently shown to be associated with reduced mortality risk in the UK Biobank18. Thus, we wondered whether estrogen medications may extend longevity by preventing menopause-induced accelerated aging of organs. We grouped all post-menopausal estradiol/oestrogen medications together and identified 47 women with normal, early, or premature menopause (but not late menopause) who were treated with estrogen by the time of blood draw. We subsetted our analysis to women among these menopausal groups and tested the independent associations of age at menopause and estrogen treatment with organ age gaps using linear regression. Interestingly, women with earlier menopause were age accelerated across nearly all organs, in line with the well-documented adverse health consequences of early menopause19 (Fig. 4c). Conversely, estrogen treatment was associated with more youthful immune systems, livers, and arteries suggesting intervention with estrogen treatment may protect these organs from menopause-induced age acceleration resulting in extended survival (Fig. 4d).”

While I applaud your post here, there are clearly caveats that you might consider adding. For instance, my post-menopausal wife, who has among the healthiest lifestyles, nutritional choices and yes, even great brain and immune health of anyone I know, just was diagnosed with breast cancer, specifically an estrogen-positive cancer, meaning that her cancer is fed by, and may even be said to be caused by increased levels of estrogen in the body. In fact, many women in this category are given estrogen-REDUCING medications to lessen their cancer recurrence risk, if they survive the original cancer. You would do a great disservice to women who are in this category by giving them the impression that an estrogen-boosting medication can add longevity to their lives. Reader beware, and someone needs to run the numbers on things like the propensity of estrogen to SHORTEN lives in certain populations, vs the thesis of increasing lifespan.

Interesting. Particularly the notion that ibuprofen could be categorized as a supplement. I wonder if there’s been any studies on benefits of this long term vs deleterious effect on the stomach, another organ that has a finite operating limit affected by stressors such as this. Ibuprofen is one of a collection of NSAIDs, perhaps one of the milder ones hence maybe the less risky inclusion in the category of ‘supplements’….but still curious.